Tech News

Analog Computers May Be Coming Back, But What Are They?

Key Takeaways

When you hear the word "computer" your next thought is probably something like "digital", "electronic", or "binary." However, anything that can compute is a computer. Digital isn't the only game in town! Analogue computers have started coming into their own, and in the future you might see this technology complement the computers we see today.

What the Heck Are Analog Computers?

Digital computers, like the one you're using to access this website, use binary data. Everything a digital computer does can be reduced to a string of ones and zeroes. So no matter what, you can always chop something digital into little pieces. Whether that's an audio recording or a picture.

Analogue computers don't work with discrete values like a one or a zero. Instead, they use a continuous variable signal to do their jobs. This could be the level of fluid in a series of tubes, voltage levels, or mechanical movement. They use physical matter to directly represent a problem, and manipulate it to reach a solution.

The oldest known example of an analogue computer is the Antikythera mechanism, which was a device used to model the solar system mechanically. The most famous modern example is the 1949 MONIAC or Monetary National Income Analogue Computer. This computer used fluid to model the flow of money in an economy. For example, one tank represented the UK's national treasury, and "money" would flow from it to other parts of the economy and back again. You could model different economic polices by modifying the flows from various tanks and see how those changes would affect the economy.

With the development of digital computers, and especially integrated circuits, analog computers have been little more than a curiosity, but as the challenges of computing some types of problem become clear, we might be entering a golden age for analog computers soon.

Some Things Are Too Complicated for Microchips Alone

Despite the incredible advances in digital computing, certain tasks remain dauntingly complex. Digital computers excel at crunching through huge volumes of data quickly and accurately, but they’re fundamentally limited when it comes to simulating chaotic or non-linear systems. This is where analog computers shine.

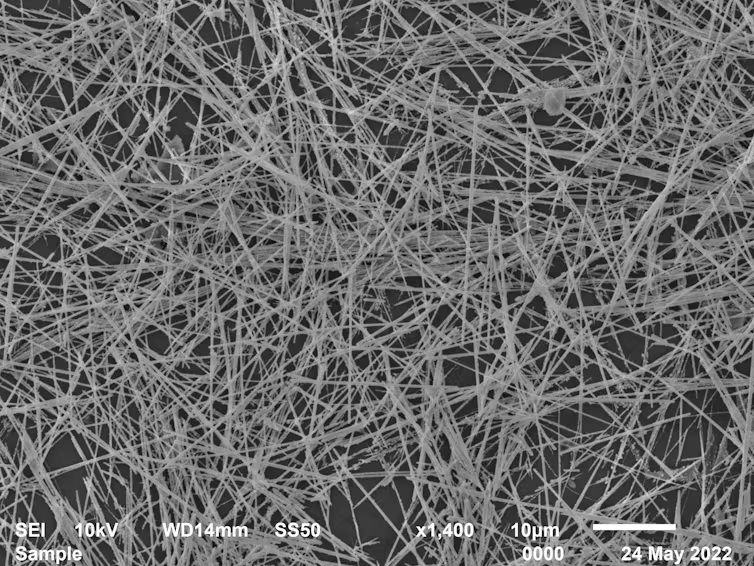

Think about how we're using digital computers to (crudely) simulate how neural nets work. It takes a huge amount of energy, and massive amounts of computation power. So instead, researchers built a "brain" using silver nanowires. The wires represent neurons in a neural net directly, they aren't a simulation in a virtual digital space. It turns out this is much more energy efficient and computationally, there's no overhead in the traditional sense, because an analogue computer "computes" itself.

Thanks to advances in materials science and manufacturing methods, we can now build analog "chips" that are a digital and analog hybrid. The analog circuits inside are designed to solve one problem or a small set of problems efficiently, and the digital parts of the analog computer let you control and monitor the analog inputs and outputs, while delagating work to digital or analog processors.

Heuristics, Algorithms, AI, and Your Brain

Analog computers are also important because there are plenty of problems that don't need to be solved to within a decimal point, and when we're looking at outcomes that are explicitly "fuzzy" digital computer might be the wrong choice in the first place. While I'd hesitate to compare mammalian brains as a whole to any sort of "computer," there are definitely sub-components of our brains that are essentially complex analog computers evolved to solve specific problems. Brains process information, and we call this "cognition" rather than the sort of programmed process a digital computer uses, but the parallels are hard to dismiss.

Humans and other mammals use "heuristics" which are energy-efficient, mostly accurate shortcuts that save on the time and energy of intense cognition. Heuristics lets us react to things quickly without thinking. Some seem to have evolved, and others are developed through learning. Computers use algorithms, which are intense step-by-step processes that lead to certain outcomes. Both have their place, but heuristics are a good fit for our slow, but incredibly parallel wetware. Analog computers offer a way to bring heuristics to our computing, or to find very energy-efficient ways of giving algorithms a physical, non-digital form.

The Future of Computers Is Mixed

Several companies are developing computing projects that are neither purely digital nor strictly analog but represent a powerful combination of concepts from across the spectrum. Take Intel's Loihi 2 project, for example. These "neuromorphic" chips are designed to simulate biological neural structures in hardware, allowing robots to experience sensations or creating chips that can detect smells. While these chips mimic the structure and function of neurons, they operate using physical artificial neurons rather than fully digital simulations. This approach allows for more efficient processing of tasks related to sensory input and decision-making.

IBM’s TrueNorth chip is another promising neuromorphic design, aiming to bridge the gap between digital and analog computing. While it operates using digital processes, the chip's architecture is inspired by the brain’s neural networks, making it a hybrid model that takes advantage of both digital and analog concepts.

And it likely won’t stop there. Emerging types of computing, such as DNA-based computing and quantum computing, may soon be integrated with traditional and analog approaches to tackle a wider array of problems. While digital computing jump-started these innovations, it’s possible that future devices—perhaps even your smartphone—will contain tiny analog components that function more like a metal brain than a conventional processor.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Zhu

et

al.

Zhu

et

al.

Comments